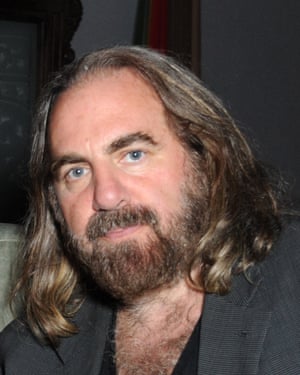

Mark Ronson

Amy Winehouse, Adele, Paul McCartney

“It’s impossible to go into a studio and not have traces of what the Beatles did with George Martin. The very idea of taking a three-minute pop song and having the urge to put something more sophisticated on it – a string arrangement or a harpsichord or a choir – he brought that to pop music. I was in a studio last night with a bass in my hand, thinking, ‘What would George do?’ Every day you go in a studio, what he did with the Beatles is hanging over you as a barometer of trying to make a good song an extraordinary one.

“He made music more sophisticated, although there is a grittiness to those recordings; it’s not all clean and perfect. He always knew what a recording needed – he introduced backwards tape loops; he was an amazing arranger and he knew how to deal with fragile egos. He could coax the best out of these audio novices who became the most prolific and gifted songwriters of all time. It’s impossible to overstate what he did in terms of trying to make something interesting or eccentric or weird.

“Listen to Tame Impala, whoever – we’re all in debt to that guy. People asked, when I worked with Paul McCartney on his last album, ‘Are you nervous?’ You’re not only nervous because you’re working with Sir Paul McCartney, one of the greatest songwriters ever – there’s also the ghost of Sir George.”

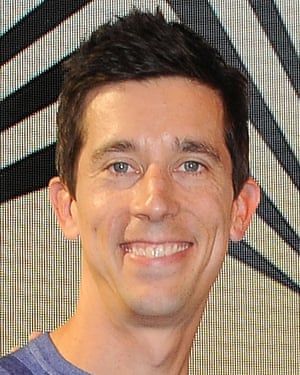

Arthur Baker

Afrika Bambaataa, New Order, Bruce Springsteen

“I was interested in production from an early age and the Beatles’ Rubber Soul and Revolver albums were really important, soundwise. And Sgt Pepper was such a produced album, with its story and characters; it was like a musical or rock opera before [the Who’s] Tommy. As a kid, you’d hear it and go, ‘Wow, what’s that?’ Then you’d go back and re-examine the records, and knowing that they were done on four-track – it’s insane.

“George was as important as anyone in the band. Without him, the songs would have sounded very different. He brought the classical element, the strings, the panning. It’s interesting to compare Phil Spector’s Wall of Sound – a mash of sound – to George Martin’s approach, where you could hear everything with total clarity. Spector was more-more-more; Martin was less-is-more.

“Anyone making music of my age would have been influenced by his production. His records blew your mind. They drove Brian Wilson crazy and influenced the Stones. Even the orchestra hit on Planet Rock was from the Beatles. What did I learn from him? Panning is important, don’t be afraid of an orchestra, and let the drummer play.”

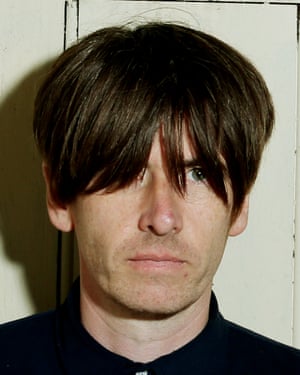

Stuart Price

Madonna, the Killers, New Order

“One of George’s greatest talents was his ability to not be heard on the records he produced. He was such a powerful craftsman; he was able to take the song in a direction that was right for the song. You didn’t so much hear him on it as the excellence at the end of it. That’s a hallmark of his work. It’s very pristine on the one hand, but it also has a real human quality to it, so whatever the act is, you hear the truest representation of them as they actually are, presented on the record.

“My favourite work of his is Live and Let Die by Wings, a record where you’re using all these instruments occupying all these different spaces, with everything from a full orchestra right down to the bass guitar and drums. Those are instruments that occupy different acoustic spaces, and it’s very hard to fit those all together and make one cohesive record. There’s a real mastery in the way that record is arranged, recorded and performed.

“One of his biggest legacies is the way he changed the role of the producer from an administrative job of organising studio sessions into a creative role. Without that, you wouldn’t have got someone like Brian Eno, who took that concept further – the producer as someone who temporarily joins the band. A producer is somewhere between director, friend, therapist, musician and engineer. And George Martin is the guy who made that OK. He made the relationship between artist and producer far more collaborative.

“He invented the idea of the studio as a place to take music that was more esoteric than could be achieved on stage – the studio as instrument. That’s what I learned from him – I’ve always tried to make things better, more accomplished and complete. That pursuit of perfection is very George Martin.”

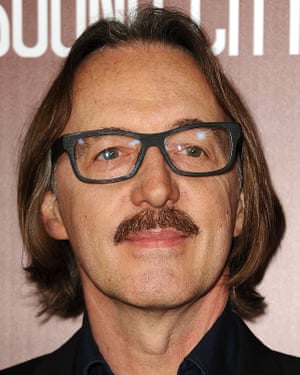

Paul Epworth

Adele, Florence and the Machine, U2

“He was the first producer I ever became aware of. Ask a member of the British public to name a record producer and they would name George. I learned from him that anything is possible if you can make it work. The fact that we use phasers, flangers, double-tracking in every single production we do – that’s down to George. The fact that I have a recording desk that was in Abbey Road and was used on those Beatles sessions is testament to the fact that it’s still some of the best equipment ever made, in some of the best hands, with some of the best ears.

“Up till him, the A&R man would produce the record – George was part of that transition, where suddenly things became more creative, which was a by-product of him being in charge at Abbey Road.

“I was a tape op for him about 20 years ago. I had just started my first proper studio job after two years working in a demo studio in Harlow. I sent out some CVs and got a job at his Air Studios. I remember him saying: ‘I’ve got this great idea: why don’t we put the orchestra through a low-pass filter?’ This was before Daft Punk’s Discovery – he was thinking along the same lines, independently.

“As a singular moment of production genius, I would choose A Day in the Life, or Tomorrow Never Knows, which still sounds like a futuristic piece of music. I don’t think the Beatles would have existed without him, because he signed them, and because he had this long-lasting relationship with them. He defined the role of the modern music producer.”

Trevor Horn

Yes, Frankie Goes to Hollywood, Paul McCartney

“The Beatles were so lucky, man. Imagine if they had got Phil Spector. Instead, they got George Martin – and he was brilliant! I couldn’t have not been influenced by his production because, when I was 15, With the Beatles was the best record of all time. I grew up listening to his tricks.

“He influenced everybody. But he was never overbearing. All you have to do is listen to The Long and Winding Road – Martin would never have done a string arrangement like the one Spector did. It wouldn’t have been as flowery, more leftfield. And the string arrangement on I Am the Walrus changed history. George got a lot of it from John Lennon’s original demo – and that’s good production. Using as much of the artist’s original idea as he can.

“Listen to Let It Be … Naked – that’s the Beatles without a producer. It’s a bit dull. Whereas Strawberry Fields Forever is one of the best pieces of music ever. Joining two pieces of music together, in different keys and at different speeds? You’ve got to have an instinct for it. It’s an art. There are no formulas they could teach you to make something like the Goons’ I’m Walking Backwards For Christmas. There’ll never be anyone like George again.”

Bernard Butler

Duffy, Tricky, Paloma Faith

“What George Martin did that was important was to say, ‘What if?’ That’s the biggest question a producer can ask. That’s what he gave all the mugs like me who came after: what if you take something and make it something else? George Martin took a group, a rock’n’roll band, four scruffy blokes in a room with primitive instruments, and thought, ‘What could you do with these personalities?’

“Producers often don’t have a vision beyond what is in front of them, but they should be able to see a piece of music as a record on someone’s turntable in a kitchen somewhere. That’s the key thing Martin brought because, before him, a producer would just put the musicians together and record what happened. George said: ‘What would happen if we made this something else?’ He was like an impressionist painter, squinting his eye and imagining what could be. It was the same with Martin Hannett: he took a punk band, Joy Division, and said: ‘What if they weren’t a punk band? What if they were something else?’

“People have said Martin took Strawberry Fields and cut the tape and added varispeed, which is loosely true. Actually, he wouldn’t have taken out a razor blade; he was the facilitator. He said to John Lennon: ‘You might be on to something here and I’m going to get the man to do it. I know the right cellist, the right engineer.’ That’s what great producers do: facilitate, find a way, get the right engineer or harpsichord player or choir and make it happen.

“Every producer has learned from him: the effects he used, the double-tracking, reverb, adding keyboards. All that revolutionary trickery is used on a daily basis now. But because he was seen as such a straight, jolly English fellow, the genius of his imagination gets overlooked. If he had worn shades and had the right haircut, he might be seen in an edgier light.”

Jeff Lynne

ELO, Brian Wilson, the Beatles

“George Martin was a big hero of mine, my favourite record producer. There were millions of questions I would have liked to ask him. It’s so sad that I won’t get to ask them now. I only met him a few times and I was always in awe of him. His productions were brilliant. He created his own sound.”

Daniel Miller

Mute Records boss,

DIY synth pioneer

“When I was nine or 10, I had a Goons EP which had The Ying Tong Song on and I’m Walking Backwards For Christmas. I wore that record out. I had no idea who George Martin was or what a record producer did. It’s got so many strange sounds, things sped up, explosions, all sorts of imaginative sounds. I still find it incredibly innovative, the way they were manipulating tape. He also did Bernard Cribbins’ Hole in the Ground, which was another favourite of mine.

“I grew up with the Beatles and my teenage years were in the 60s. From Me to You and Please Please Me, especially, just exploded out of the radio; they sounded like nothing on Earth. The way they leaped out of the radio was beyond even Elvis. The impact was massive.

“I Am the Walrus, Yellow Submarine, Strawberry Fields – those songs could have gone in any direction and somehow, between the Beatles and him, they honed a special sound that nobody has really replicated. It’s a particular atmosphere that was so much in tune with the time.

“He was the one directing the engineer, making the band’s ideas possible. He was an inventor, exploring new sonic areas that nobody had explored before, using limited equipment. And that started with the Goons.”

Butch Vig

Nirvana, Garbage

“As far as I’m concerned, he’s the most important producer in the history of rock’n’roll. Early on, a lot of a producer’s job was simply to capture a recording. But George Martin totally changed that. He encouraged the Beatles to start writing these complex vocal harmonies – they’re what grab you, beyond the band’s energy.

“His production has never dated, and his string arrangements were groundbreaking; they never sounded schmaltzy. Listen to Yesterday or Eleanor Rigby – the strings are quite dark and brooding. There’s a lot of rhythmic movement in them, too, especially when he suggested no drums or bass on Eleanor Rigby.

“He invented modern production: the idea that you could use the studio as an instrument, to look at it as a place to experiment in, you don’t have to just record something au naturel. So many of his ideas we hear on the radio now and have influenced me: effects on the vocals, flipping the tape around and recording backwards guitar. He started speeding up tapes and slowing down tapes, changing the pitch on things …

“He was also very fastidious about how he wanted to hear things. Because everything had a great clarity to it. I can’t tell you how many bands I have worked with who would bring up Martin’s production techniques. There was a point where I wanted Kurt Cobain to double-track his vocals on a song when we were recording Nevermind, and he was reluctant to do so because he thought it sounded too fake and I said: ‘Well, John Lennon double-tracked his vocals.’ And as soon as I said that, Kurt said: ‘OK.’ He pretty much double-tracked all the vocals after that.”

Nigel Godrich

(Radiohead, Beck, Paul McCartney)

“The story that Paul McCartney told me was that John Lennon was out all night doing whatever and showed up pretty frazzled the next day with Tomorrow Never Knows – but it was a song with just one note on the guitar and some singing. And George Martin said: ‘OK, let’s see what we can do with this.’ It’s taking something very basic and seeing the potential in it and using your skills to make it happen. It’s a cross between a group therapist and a film director.

“We had Joe Meek and other producers, but George Martin produced the job of producer – he made that job. It was a time of great revolution and technology, multi-tracking and what you could do in a studio. He had all of these things at his disposal.

“I love the guy – he was an amazing inspiration. He wrote a book, All You Need Is Ears, and it changed the way I thought about recording in terms of simplicity and directness, just before we recorded Radiohead’s Kid A. And I was lucky enough to meet him. He was very kind to me, very humble, and I know his son well. His work will be alive for a long time. Listen to Let It Be - the Phil Spector version – and Let It Be … Naked. You can hear how different they would have sounded without him - messy and unfocused. It’s the end of an era.”

Comments